How to get a book deal when you're not famous

Or, how Edgar Allan Poe helped me get a book deal and could help you, too.

A couple of weeks ago, I was talking to my old L.A. writers group via Zoom, and it came up how damn near impossible it is these days to get a book deal.

A book deal, in this case, to mean a traditional, “Big Five,” New-York-publisher-with-an-office-on-6th-Avenue kind of book deal. Most people know that it’s easy to self-publish a book on Wattpad or Kindle. But to convince an outfit like Simon & Schuster or Little, Brown to publish your novel or work of nonfiction? That’s like trying to win American Idol, and I don’t think that show is even on the air anymore—making it all the harder to win.

So I thought I would share, here, a little-discussed hack that helped me get a traditional book deal in the fall of 2019. Not a deal that made me rich or anything, but still: my childhood dream, stamped like a parking validation! What a thrill, especially before I realized how much work would be involved.

First things first, though. Why is it so hard to get a deal?

A better way to phrase this question might be, why is it so hard for an ordinary, non-famous person to get a book deal? Because famous people have no trouble. If you’re a Kardashian or a comic with a Netflix special or even a momfluencer with 500,000 Instagram followers all breathlessly awaiting your next inspirational quote, then it’s not that hard.

For the rest of us, those without massive platforms or perhaps any platform to speak of, it’s extremely, extremely hard, because the publishing industry thinks it can’t afford to take a chance. The big houses, these days, are more in the business of running proven winners than fresh horses. It’s such a tough business environment for them that they’re simply not willing to put money and effort into books they’re not sure will sell. And sell a lot. As in, at least 10,000 copies and, preferably, much more than that.

This means that there’s effectively almost no chance that you—ordinary, aspiring, non-famous writer you—can sell your book.

Of course, exceptions to the rule exist. And the usual entrenched advantages—having gone to the right school (an Ivy or Iowa), having elite connections, and/or having some big, noteworthy job—matter, too. One way or another, brilliant new writers emerge every year. In general, however, an ordinary person trying to get a traditional book deal is much like an ordinary person buying a lottery ticket and hoping against hope. It could happen. You could pocket the $200 million. And hell, I’m probably underestimating the odds a tiny bit. But make no mistake, they are long.

Back in 2019, when I sold a nonfiction book proposal, I didn’t set out to game the system. What happened was, after a dozen years of writing novels and trying to find an agent who might want to represent me, I fell into a horrible depression. Then, for the first time since I was a kid, I started reading Edgar Allan Poe. For about a month straight, I just lay around reading Poe and crying, mostly in my bathtub, because I was in a dark place and also because, all of a sudden, the metaphorical nature of Poe’s short stories had become clear to me. Holy shit, I thought. He was talking about depression and despair the whole time.

The ships captained by ghosts, the yawning whirlpools, the whistling scythes? All that stuff was just window dressing. Poe was talking about two things at once. On the surface, shipwreck or, say, torture by the Spanish Inquisition. Below, awful existential pain, the same kind that was plaguing me.

I started digging through the numerous biographies about his life, and though Poe’s life was indisputably a dumpster fire, just incredibly sad to read about, doing so had the strange effect of cheering me up. Look at everything he lived through, I thought; he still got his work done. He still managed to keep going despite, well, everything. And he’d even cracked some pretty good jokes all while. I loved reading Poe’s letters in which he bitched—endlessly, bitterly complained—about his day jobs.

Poe was funnier than he ever got credit for, I thought. No one knows how funny he is.

Soon enough, a realization hit me: I was the only person ever, in history, to really understand Edgar Allan Poe.

Obviously, that was a delusion. But it’s a common one. Since Poe’s death in 1849, hundreds of books and thousands of articles have all been written by people suffering from this delusion. Poe just has that effect on people. He’s such a complex figure that, once you Hoover up enough facts and you’re finally able to bring him into focus in your mind, you start to think you’re the only person who truly gets him.

I was having a drink with a historian friend one night and I told him about all this: how Poe was cheering me up, how I’d come to see him as a kind of flawed-yet-fascinating existential hero. Plus a few words about my being the first and only Poe Understander in history.

“That sounds like a book,” my friend said, lifting his glass.

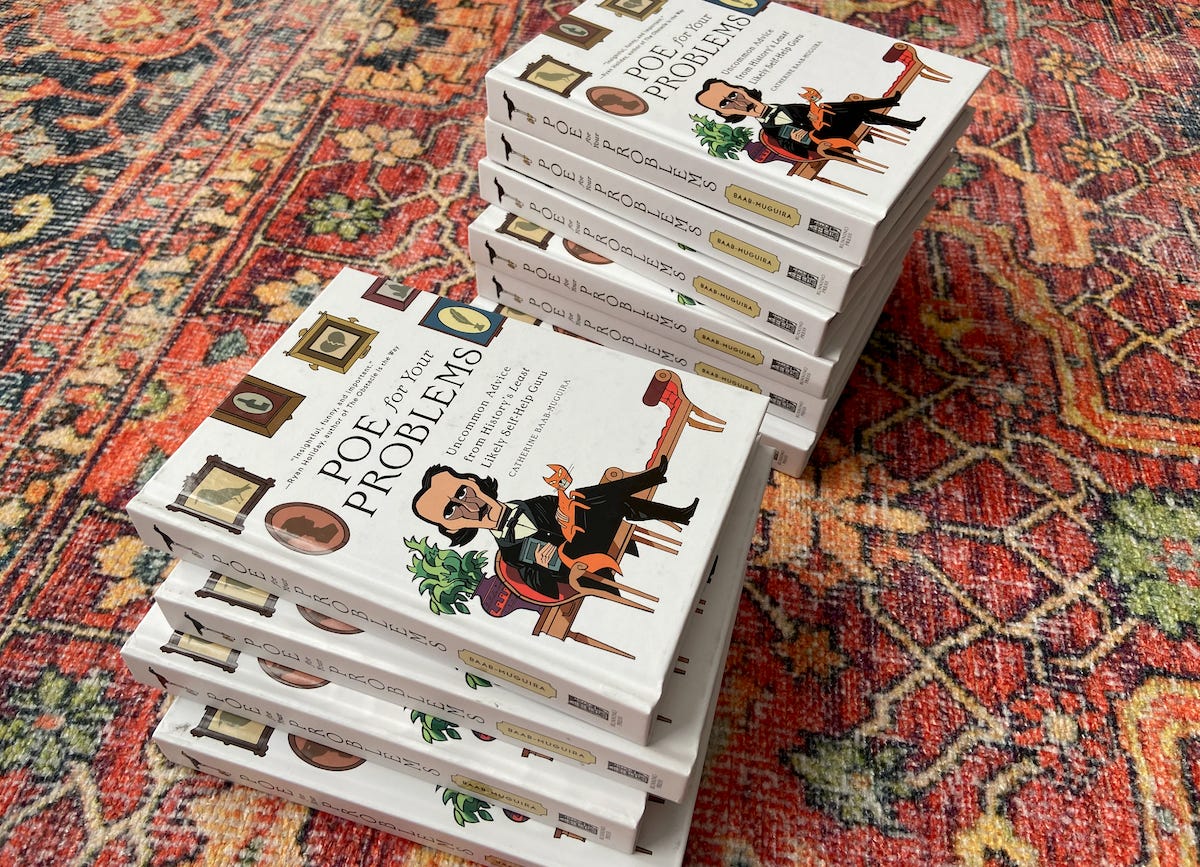

“Oh yeah,” I deadpanned. “I’m going to write a book about reading Poe for self-help and call it How to Say Nevermore to Your Problems.” Which turned out to be just the working title.

Over the next year, I roughed out a book proposal. (A book proposal is essentially a 10,000-word sales pitch for publishers that details what a nonfiction book will look like and who might buy it. This is how most nonfiction books get sold. You write the proposal first, not the book itself.)

Next, I sent query letters to agents, hoping someone would want to represent me and my Poe idea. This time around, I got offers. And while it took another eighteen months to find a publisher for the book, and I had to rewrite my proposal from top to bottom three different times, my book proposal eventually went to auction, with Running Press, a subsidiary of Hachette, bidding the most and winning.

So what changed?

I still wasn’t—obviously, still am not—famous, and wouldn’t want to be. Who would? Most adults agree that, while some money might be welcome, the other aspects of fame seem horrible, essentially life-ruining, right? Meanwhile, I continue to suck at Twitter and have few followers. I still don’t have any large platform to speak of. I publish freelance articles sometimes, but that’s nowhere near enough of a public presence. At least in my experience, it’s not even table stakes.

But none of this mattered much anymore because I was writing about someone who has a massive platform. Poe has four million Facebook fans. He may’ve died 171 years ago, but he’s so well known, beloved and influential today that not only is there an entire academic discipline known as Poe Studies, but people get tattoos of his face. People cosplay as Poe at Comic Con.

Most importantly, you can put numbers to Poe’s audience: the 4 million Facebook fans; the 63,000 people following the Poe topic on Quora; the 22,000 fans on the official Poe Wattpad page; the 3,500 folks following the Poe subreddit. In other words, you can “prove” the appeal.

The book-deal hack I stumbled across unwittingly

You don’t have to be famous to get a book deal if you write about someone who IS famous.

Or maybe you write about a famous phenomenon. Maybe you write a nonfiction book about side-hustles or Cross Fit or crosswords or coding or knitting or whatever, so that it matters less how many fans YOU have, and instead a publisher will look to how many fans there are of your TOPIC.

You do still need some experience as a writer. That’s when your previously published work comes in handy, and all your relevant work experience and life experience starts to matter.

This hack applies especially to nonfiction, of course, but I could see it being relevant for fiction writers, too. Maybe you write a short story collection about Princess Diana, and how she faked her own death to escape the press and now works in a legal pot shop on Santa Monica Boulevard. Or you write a historical novel about Biggie in the ‘90s, or, I don’t know, you write a musical about Alexander Hamilton.

Any of these gambits would allow you to make the claim that there’s already huge public interest in your subject. Then you basically just point to that interest and say, “there’s the audience for my book.” Instead of going on about your own platform, you can detail the platform that your subject, your topic, already has. My own 10,000-word book proposal basically boiled down to: I’m a Poe fan who buys books about Poe. I think other Poe fans will buy this book about Poe.

Now, maybe this hack has occurred to you already. Maybe it didn’t take you the last dozen years to puzzle out. What’s that saying, “learn slowly, then you’ll know”? That’s my process. I hope your process is quicker and more fun, and less naive and absurd. In any case, if you want to write a book, you could do worse than beginning with the famous thing, famous person, that you’re obsessed with. Surely you’re obsessed with something?

A good link

If you’ve got a subject or topic already in mind, then as a next step, maybe check out the following link. It’s only a random LinkedIn post, yet it contains some of the best writing advice I’ve ever come across. And the advice also applies to marketing and pretty much every other creative endeavor. Here it is: “The Secret to Coming Up with Ideas People Can Get Excited About.”

(I don’t know the guy, or much about what else he publishes. I just like this post.)

Thank you for reading. Wishing you luck in your efforts to get published, or whatever the goal looks like in your creative discipline,

Cat

What a great idea! Another reason why so many writers like Poe, and it's tragic: He labored so long and yet his fame came posthumously. Little did he know the Mystery Writers of America would give out awards called the "Edgar," the mystery-writing equivalent of an actor's Oscar. And it would be a little bust of the man himself, a cherished object.

I'm a mother of a student that went through the Apalachee high school shooting. I'm currently writing about that. I've been in contact with the shooter father who is also being charged. I will eventually be in contact with the shooter. I'm coming at this with the angle of 'trying to not be prejudice, but respect my feelings' because I'm going to ask the hard questions. Can you push me in the right direction to getting a publishing deal so I can continue to dig into the minds of the school shooter and his family?