Why your platform is really a savings account

A Q&A with Leigh Stein about publishing novels and hedging the literary apocalypse

Hey folks. Welcome back to Poe Can Save Your Life. It’s been a little while—a rough few months, as you know if we’re Instagram friends—and I appreciate you sticking around.

Today’s post concludes my series of interviews with writers about how they broke in and how YOU can break in, too.

It seems only fitting that the series would conclude with the one creator-economy-career thought that has, for the last 12 solid months at least, been ringing and clanging in my brain like the opening bell of the New York Stock Exchange:

NO CONTENT MODEL LASTS FOREVER. SO BE PREPARED TO ADJUST.

By “content model,” I mean an era’s prevailing media form. For instance, until very recently, it was a big big deal to contribute to the NYT, the WaPo, Jezebel, Teen Vogue, The Guardian, The Cut, et all. You could launch your career that way. You could get a book deal. I know this firsthand.

And now? That route still exists, sort of, but it’s a lot less reliable than it once was—and here’s where I start to fan girl and tell you that no one on earth is describing this shift more intelligently and helpfully than Leigh Stein. No one’s covering it more generously and artfully. No one’s writing a better newsletter. No one!

In the Q&A you’ll find below, Leigh talks about her career to date, explains what it was like to be “the last girl they let into” the trad, $3-a-word publishing party, how she’s since pivoted to TikTok and platform-building, and her #1 tip for you. Don’t miss it.

Leigh, you've got a fascinating background, so let’s begin at the beginning. Where’d you grow up, how’d you come to writing?

I grew up in a middle-class suburb of Chicago. My childhood dream was to be left alone, at home, to write poems and make crafts and go on the internet, and I have achieved this dream. As an adolescent, I struggled with depression and anxiety, and an online friendship saved my life. I dropped out of high school halfway through junior year. I was always writing, but my creative writing was never encouraged by teachers, so I seriously pursued the two things I was told I was good at: acting, and competitive classical singing. As a teen, I was also publishing poetry and short fiction on Livejournal (a blog).

I moved to New York City at 18 to attend an acting conservatory. When I got there, they said, “We never received your high school diploma.” I said, “Oh, I don't have one.” They were like, “We're a college?” Whoops! They let me stay as long as I promised to pursue my GED, which I did. That year, I had my first story published in an online lit mag and I realized that I still preferred being alone, at home, on the internet, to other modes of being, so I didn't go back to a second year of acting school. The other students had charisma that I lacked; I had a nerdy appreciation for play scripts.

In my early 20s, I wrote and published a ton of poetry. I moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, with a charismatic, troubled boyfriend, to write my first novel (and blow up my life). A close friend (whom I'd met on Livejournal) wanted to help extricate me from that toxic relationship; she heard that the cover editor of the New Yorker needed a new assistant, and told me to apply. I told her I was too depressed to move to New York, but she pushed me to send my resumé. I got the job. Again, I found myself in a bizarre situation where the HR department at Condé Nast asked where I went to college and I didn't have a BA. I worked at the New Yorker during Obama's 2008 presidential campaign, which was an extremely exciting time to be at the magazine.

I love this—your candor, the poetry/dropout/theater/blowing up of one's life stuff. How’d you get a deal for your first novel?

I was still working at the New Yorker when I received an email that changed my life: a literary agent had read my blog, where I'd posted about my novel. She must have found me through my published poetry. She asked to see what I had of the novel, and for a synopsis. I don't think I'd finished the manuscript yet, because I remember having to make up an ending for the synopsis. I think having an agent interested in my work definitely motivated me to finish the book. She became my first agent, and she went on submission with the novel in the fall of 2009. It got tons of glowing rejections. The timing was bad. My novel was about a depressed young woman who moves back home after graduating college and takes a babysitting job, but I was ahead of my time—we weren't yet feeling the shockwaves of the market crash. Editors didn't know what to do with a novel with a 22-year-old protagonist. Was it YA? No.

She ran out of editors to submit to and told me I'd have to write a second novel. I thought, “No way.” I'd met the writer Catherine Lacey at a Tao Lin launch party in Brooklyn; Catherine had an internship at Melville House and she asked if I wanted her to give my manuscript to the publisher. He read it in a weekend and asked on Monday if it was still “available.” That was the end of 2010.

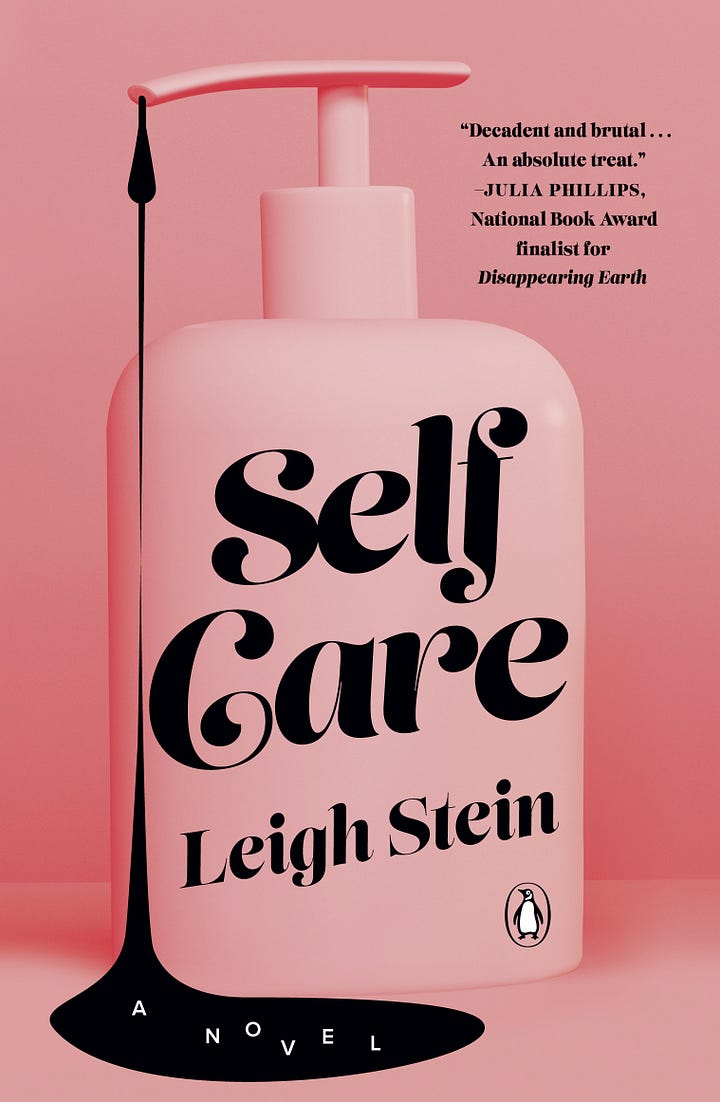

By the time the novel was published, in January 2012, lots of millennials were living at home with their parents, and the biggest TV network in Japan filmed me as the poster child of the “American boomerang generation.” The pilot episode of Girls has Hannah Horvath's parents telling her they're going to cut her off and not pay her rent anymore. I was ahead of my time when my novel was on submission and then right on time when it came out; the same exact thing happened to me with Self Care.

Magazines still existed in January 2012, and I was very lucky to get reviewed in the print editions of O Magazine and ELLE, as well as an interview in Time Out Chicago (where I'm from). I got paid $3 a word (!!!) to write a “beauty” essay for Allure Magazine about how my ears stick out. I got sent on a multi-city book tour that my publisher paid for (!!!). I was like the last girl they let into the party before they turned the lights on and told everyone to go home, you're drunk.

How did the market shift between the time when you published The Fallback Plan and when you published Self Care? What big changes jumped out at you?

Between 2012 (when my first novel came out) and 2020 (when Self Care came out), I watched a shift from publications launching, or making, writers to social media making writers. I just grabbed Bad Feminist (2014) off my bookshelf to flip to the acknowledgments: those essays previously appeared in The Rumpus, VQR, Ninth Letter, Bookslut, Jezebel, the Los Angeles Review, BuzzFeed, and Salon. I sold a memoir in 2015 because of a viral BuzzFeed personal essay. Today, pitching and publishing essays in digital media outlets gets you nowhere. Your time and energy is much better spent building your own audience. Rayne Fisher-Quann has 87,000 subscribers on Substack and she sold “a collection of essays that blend memoir and cultural criticism to chart a path through the essential strangeness of modern womanhood” to Knopf in August of last year.

This effect has been much more impactful in non-fiction publishing than fiction, and it's still true that you don't need a platform to sell your novel to a publisher. That being said, if you sell a novel to a publisher without a platform, what's your plan for marketing your novel when it comes out? How will you sell it to readers, if you don't have an audience? There are a lot of bitter novelists out there, angry at their publishers for not making them a success.

I see my platform as a kind of savings account, as a hedge against future calamity.

I think you are COMPLETELY CORRECT. Given all that, what's your biggest piece of advice for writers who want to get a Big 5 book deal?

My biggest piece of advice is to read a lot of recently published (last 3 - 5 years) books in your category—that's a great way to learn the market, and it's free if you do it through the library. I'm always astonished by the number of writers who take my publishing classes who can't name any books that are similar to their own; they think their ignorance demonstrates the uniqueness of their own book, but it's a red flag that they aren't paying attention to the industry they want a career in. I once heard Carly Watters say, about the agent querying process, “You're trying to monetize a hobby.” There will be other writers who'll tell you, “Just write the best book you can and don't worry about the rest,” but I've seen too many writers spend years of their lives on projects they assumed they could sell, without ever learning the market. I think you've got to do both, simultaneously. Earning real money for your art is extremely difficult! Some people want the government to do more to subsidize artists. I choose capitalism. I'm trying to write books that are provocative, meaningful, timely, and funny, while also being accessible enough to be popular and commercial. This is the insane endeavor to which I've chosen to dedicate the rest of my working life. Wish me lots of luck.

Go here to check out Attention Economy, Leigh’s fantastic newsletter. And find her latest novel, Self Care, right here.

A good link

See here for the earlier interviews with the memoirist Darius Stewart, the romance novelist Holly James, and the comic novelist Andrew Boryga.

Have you heard The Altons? I was in Richmond’s Jefferson Park a couple weeks ago and a very good self-appointed DJ was blasting this song from a big speaker he’d heaved up onto the lip of the fountain. Perfect sort of summery song.

I wrote about frontier theory for Quartz.

As always, I’m wishing you the best of luck as you look to break into that field you’re looking to break into. And thank you for reading. If you’ve got any questions about how to find “comps,” re: Leigh’s #1 tip for you, shout in the comments. Happy to help.

Cat

Thank you so much Catherine!

How true!