Writing secrets of a heavy metal frontman turned bestselling author

Talking books with Randy Blythe

Folks, here’s my year in review: It wasn’t great!

If you caught my last post, you know the broad strokes (and if you didn’t, let’s just say this year has been full of challenges I wouldn’t wish on anyone). But it hasn’t all been grim—there have been moments of connection and inspiration, too. One of those was the chance to talk art and issues with someone whose work and outlook have profoundly moved me: Randy Blythe.

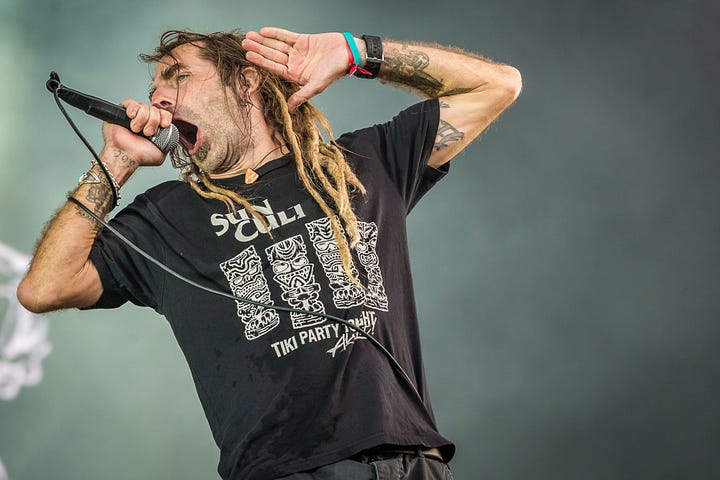

You might know Randy as the frontman for lamb of god, the legendary heavy metal band that’s been raising hell for decades. What you might not know is that he’s also a bestselling author.

His first memoir, Dark Days, chronicled his harrowing experience being imprisoned—and later, exonerated—for manslaughter in the Czech Republic, every stage of which made international headlines.

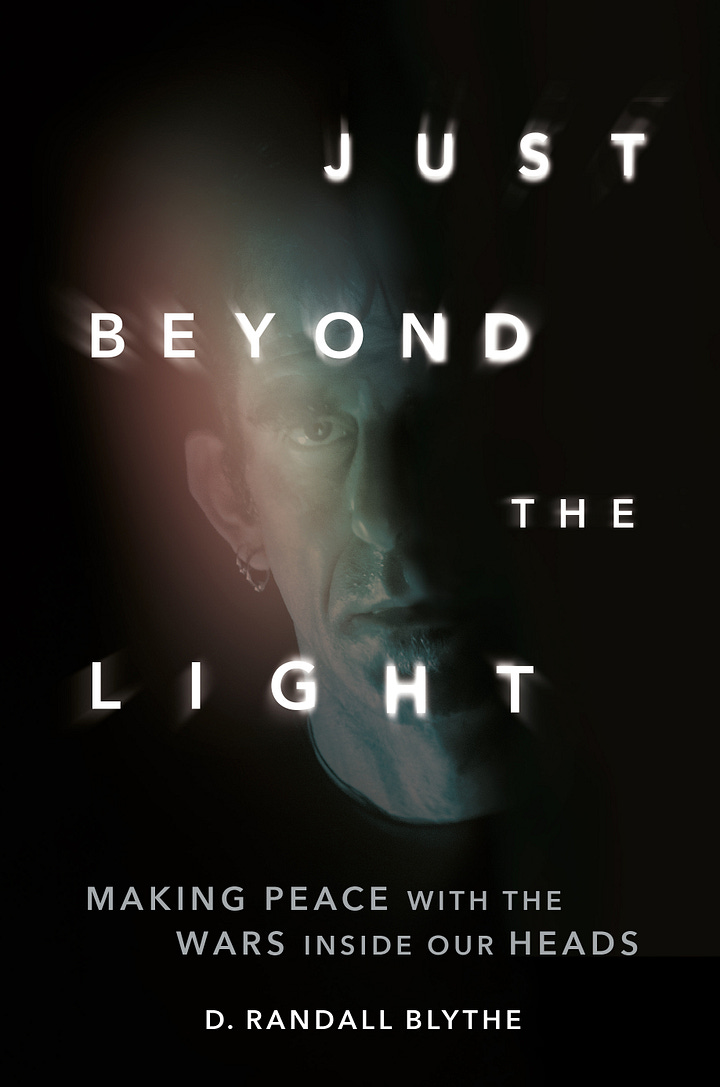

His forthcoming second book, Just Beyond the Light, digs even deeper into his singular mind, tackling sobriety, creativity, and mortality with a frankness and wit that’s already drawn comparisons (from me, anyway) to the likes of Geoff Dyer.

In the interview you’ll find below, Randy speaks about the discipline of art, the dangers of brain rot, and the struggle to make something real in an increasingly artificial world. And if I’m right, Randy’s honesty will move you the same way it moves me. Truly, there is something so heartening about someone being way more self-reflective and kind than their success and visibility otherwise demand.1

He might even inspire you to wrestle your own blank page into submission. Let’s get to it.

Randy, for those who may not know you, can you talk a little bit about who you are and how you came to writing?

I was born in 1971 in Fort Meade, Maryland and raised in Cape Fear, North Carolina and Tidewater, Virginia. When I was 5 or 6 years old, our television blew up after a power surge during a lightning storm. My father decided that he wanted my brothers and I to experience childhood without television, and so we didn’t own one for several years. Although we complained at the time, in retrospect I am immensely grateful to my dad for that decision, as without the distraction of TV, I fell deeply, deeply in love with books at a very young age.

The first thing I remember writing was a poem, sometime around my kindergarten year, on the porch of my neighbor’s backyard log cabin—I don’t recall what it was about, but I do remember the adults having a positive reaction to it. I continued to sporadically write a little poetry on through high school, mostly in an attempt to get girls (this failed miserably). I also outlined a science fiction novel in 5th grade, but I never took it any further. In 1989 I moved to Richmond, VA under the guise of “going to college” (in reality, to attend punk rock shows and party). My academic career was less than stellar, but I thoroughly enjoyed a poetry class under the published poet Gregory Donovan, and utterly despised a fiction writing class taught by some frustrated writer dude with permanently chapped lips. This professor constantly chastised me for not following the “rules” in the creative writing textbook he taught from, so like any self-respecting punk rocker, I said, “FUCK YOUR RULES,” and proceeded to self-publish a fanzine. I put out four issues of the fanzine, then quit when I started singing for a band, Burn the Priest, in 1995 (we changed our name to lamb of god in 1999).

For the first 15 years of my band, I didn’t write much more than song lyrics, as I had managed to develop a rather distracting case of alcoholism. I often talked about “being a writer,” as I worshipped a few authors—predictably, Hemingway, Bukowski, Hunter S. Thompson, etc. For over two decades, I did all the things those great writers did—tons of drinking, a respectable amount of womanizing, even a little fist fighting here and there. I was doing all the right writer-dude things with the exception of one minor detail—the writing part. I got sober in 2010, and started writing again, mostly blogs and a few music magazine articles. In 2012, much to my surprise, I was arrested at the Prague airport and charged with manslaughter in connection with the tragic death of a fan that had occurred after a 2010 concert. I spent 37 days in a Czech prison (I wrote a lot while incarcerated), was released on bail, returned to the Czech Republic six months later to stand trial, and was found not guilty. Shortly after the verdict, lamb of god’s booking agent pestered me until I agreed to speak with Marc Gerald, a literary agent friend of his. Marc eventually convinced me to write a memoir about my experiences, and my first book, the bestselling Dark Days, was released (fittingly enough) on Bastille Day, July 14, 2015. Almost ten years later, my second book, Just Beyond the Light, will be released on February 18, 2025.

I’m fourteen years clean and sober, and thanks to that, today I can truthfully refer to myself as a writer.

Your answer reminds me of what I enjoy so much about your writing. In my blurb of your new one, I said, “Followers of the music and of Blythe’s first book won’t be surprised at what great company he makes, but fresh fans are in for a special treat, set to discover the restless, funny, questing, heavy metal Geoff Dyer they didn’t know they needed.” It’s so damn true.

Given your unique trajectory—from fanzines to song lyrics to bestselling memoirs—how has your perspective on “the rules” of writing evolved since your college days? Do you see any connections between the discipline of sobriety and the discipline of writing?

First of all, thank you so very much for the beautiful blurb! I think Just Beyond the Light is a slightly odd book that doesn’t fit into any precise genre/category (even though I know it will inevitably be shelved in the music section of bookstores), and I believe Poe for Your Problems is a weird book as well (in the very best way), so it made perfect sense to me to ask you for a blurb. Weirdos unite! Okay, enough of the mutual back-patting.

As I get older, I gain more respect for certain structural “rules” that exist in each of the creative disciplines I pursue—music, photography, and writing. With writing, that means trying to pay more attention to effective sentence structure, correct grammar, and even to not rely on spellcheck so much. I want to internalize these standard utilitarian components, doing things correctly from the start so that I’m not dependent on a computer program or editor to fix my sloppy writing later. This is the analog, pain in the ass, nuts and bolts stuff that writers used to have to know, but that technology is rapidly stripping from us. Despite what the techno-utopians would have you believe, the new way is definitely not always the better way, so I’m attempting to relearn some of those boring old basics. This is definitely stretching the few brain cells I have left rather thin, but as the old saw goes, “you have to know the rules before you can break them effectively.”

I am also trying to brush up on my basics because I am honestly worried about the state of the English language. In 2015, the Oxford Dictionary’s Word of the Year was this: 😂, officially called the “Face with Tears of Joy” emoji. Reading about this immediately gave me a spasmodic eye twitch, filling my entire being with a blinding and murderous rage. Language, both spoken and written, should be in a constant state of upward evolution, becoming richer and more capable of nuanced expression… but the emoji? Pure moronic retrogression. It’s not a fucking word, we aren’t living in ancient Egypt, and the fact that one of the most holy repositories of our beautiful mother tongue chose a goddamned pictograph as the word of the year tells me that if we don’t start safeguarding a few rudimentary things, eventually we will devolve into communicating via a series of grunts as we poke chimp-like at our iPhone 237, one “lol,” “omg,” and 😂 at a time.

So, with writing, music, and photography I don’t think I have a problem with useful rules so much as I despise formulas being imposed on creative expression. I think formulas, while obviously commercially viable and repeatedly proven money makers (just look at the state of Hollywood), are the death of new, fresh art. Knowing the three-act story structure is useful. Knowing how to write a standard 4/4 rock banger with a verse, pre-chorus, chorus, repeat, outro structure is useful. Knowing the rule of thirds is useful for basic photographic composition. It’s good to know all of these things but being told you are doing things incorrectly because you are not precisely following one of those formulas is ludicrous—that was my problem with my college creative writing professor.

As far as a connection between writing and sobriety, they are inextricably intertwined for me. No sobriety = no writing (or really anything else, other than misery). However, while I most definitely consider writing a discipline, I do not consider sobriety to be such. Sobriety is not something I have to work very hard at; it just is my normal state of existence and has been for fourteen years now. I put in 22 years of Olympic-level drinking and drugging before I got sober—now that was hard work. Being sober is infinitely easier. I must never forget that I can go back to that misery with just one drink, but the small daily effort required to remind myself of that fact is minuscule compared to what it took to remain militantly fucked up 24/7. Being sober does not fill me with anxiety; it enables me to push through the horrid anxiety that fills me when I sit down to write.

Sobriety is a pleasure, the blank page is a motherfucker. I have to wrestle it into submission every single time I face it.

What do you see as the biggest threat to genuine creativity? You mention technology and commercial formulas, but are there other forces (cultural, personal, maybe self-imposed) that you think make it harder for artists to create something fresh?

And on the flip side, what keeps you coming back to the blank page when it feels like a battle?

There is a rapidly growing body of scientific evidence clearly pointing to the negative cognitive and emotional impact certain expressions of internet technology such as social media are having on humans (particularly our youth)—the sharp decline in reading comprehension skills, shortened attention spans, rising levels of mental illness, widespread belief in criminally stupid disinformation, etc. While this is definitely concerning, this same technology has also been used in highly effective ways for deeply humanistic and altruistic purposes as well, so it’s a double-edged sword. Worries about the possible existential threat posed by AI aside, I think the true danger to our society (which certainly includes fresh original art) is not the technology itself, but the myopic cultural framework of unquestioning acceptance around it. One of my favorite stories that illustrates this comes from 2015, when my band was in Australia playing gigs as part of a massive touring festival called Soundwave. I was sitting backstage talking with a younger band from America, a fresh-faced group of early twenty-somethings that had only been touring for three or four years at that point. They were massive lamb of god fans, asking me for some war stories from our early van touring days, and as they were really nice kids, I decided to put on my grandpa hat and hold court.

“Well, to start, things were much, much different back then. Nobody had a cellphone and there was no GPS. When you got to whatever town you were going to have a gig in that night, you had to find a payphone, call the promoter, hoped somebody picked up, find out what house party or VFW hall the show was supposed to be at, then go there and hope a few people showed up,” I said. The guitar player of the band looked at me with genuinely confused eyes, then asked me a question that has been seared into my consciousness ever since.

“Wait, wait… you didn’t have a GPS? I don’t understand! I mean, how did you guys ever know how to get where you were going?” The other band members nodded their heads in concerned agreement— they actually looked anxious pondering this dilemma.

“Well, back in the day we had this stuff made out of trees called paper,” I said, “and they made these things called maps out of it. We used those.”

We all had a good laugh, but after further discussion, I learned that no one had ever taught these kids how to read a map—not their parents, not a schoolteacher, not a scout master, no one. Why would they? They had come of age with smartphones, and step by step directions to basically any address on earth were available to them with just a few clicks on a screen. Yes, but what if they lost their phone? I thought.

This is what concerns me—it’s not the technology itself (GPS is great, I use it all the time when traveling), it’s the mass societal embrace of the easier, softer way to accomplish cognitive tasks with as little mental exertion as possible. Making new and fresh art is definitely a cognitive task that requires massive amounts of mental exertion. The best art requires a certain amount of friction, a willingness to try uncomfortable things and wander into murky and unknown territories in an attempt to push beyond the limitations our own talent and even level of intelligence. But when all the answers to all the questions are provided all the time by the incredibly powerful handheld computers everyone is glued to (the smartphone, or as I like to refer to it, “the pocket Jesus”), why would most kids ever attempt to wrack their already data-overloaded brains, deeply questioning themselves while trying to come up with something new? This utter dependence on technology to instantaneously accomplish tasks once required of our brains is accepted as completely normal now, leading to an atrocious level of intellectual sloth. This is an impediment to art.

I am not some alarmist old man shaking my fist at the sky—in English classes in schools across America, more and more teachers are assigning summaries of books instead of books themselves. Neuroscience shows that deep reading (you know, like, um, a whole book) strengthens the synaptic circuitry in our brains connected to things like critical thinking, in-depth background knowledge, and empathy. Yet in 2022 the National Council of Teachers of English released an incredible twenty-five-cent word salad of a statement about the need for English teachers to adapt their book-centric curriculum to our new media-centric word. One absolutely cranium-busting sentence read: “The time has come to decenter book reading and essay-writing as the pinnacles of English language arts education.” Ummmm... fuck you. Educating students so that they can read and write well is no longer to be seen as the primary goal of an English class? The statement went on to discuss the need for English language educators to adopt new pedagogies to help students develop skills in news literacy, information literacy, media literacy, critical media literacy, digital literacy, algorithmic literacy, data literacy—every kind of literacy except for literacy literacy—and my favorite: media production. Think about what this means for a second… in effect, a council of supposed English language educators threw up their hands and said, “Okay everybody, with all the distractions these days, it’s simply too hard for these little dummies to do the whole reading and writing thing— it’s time for us to teach them how to make YouTube videos more effectively, since that’s what they seem to gravitate towards these days. Don’t worry about all that fuddy-duddy Shakespeare stuff—the kids don’t dig it.” These were fucking English teachers—not guidance counselors, not school shrinks, not computer science teachers, not social studies teachers, not psychology teachers, not mass-com teachers—English teachers. What a horrific disservice to both our children and our beautiful language! Call me an anachronistic and short-sighted fool, but somehow, I doubt that in 400 years an English language PhD candidate will be defending their thesis on the verbal majesty of the greatest TikTok influencer of the early 21st Century. But the Bard of Avon shall endure, as long as a few brave educators do the right thing and teach students to use those magnificent brains of theirs by reading deeply and writing well, instead of bending the knee to the moronic tsunami of lightweight distraction currently swamping our culture.

It’s the cavalier acceptance of our intellectual pool growing more and more shallow with each shiny new digital distraction that worries me for artists, not the technology itself. With all the information in the world at our fingertips, we shouldn’t be getting dumber, but we are. Lack of depth has never created great art, ever.

Why do I keep coming back to the blank page? Because as previously mentioned, I want to push myself past the limits of my talent and intelligence. I want to make war on my own weakness and intellectual sloth, to become a better, more useful human being in the process. I also want to leave behind something that people can read 100 years from now and still get a laugh, because reading and writing is time travel achieved. It’s magic. It’s immortality, so there’s probably an unhealthy amount of ego attached as well but fuck it—I’d rather work hard to leave behind something beautiful than sit on my ass and stream unboxing videos as my life slowly disappears into the toxic digital toilet, one wasted second at a time. It just seems like a more worthwhile pursuit—someone’s got to fight the good fight, right?

Speaking of unclassifiable books, I called Just Beyond the Light an “intellectual road trip.” I said that because, while there are some similar fun rants in it, there's also this big, obvious but not unsubtle, open-hearted curiosity driving it all and the reader can feel that...

And that matters because, in so much nonfiction, the reader is being tendentiously railroaded into a set of conclusions and assumptions that they bought the book already agreeing with or at least anticipating. Yours is not like that, which might be my favorite thing about it.

But you tell me: What are you most proud of with JBTL, what are your hopes for it?

I think the hardest thing about writing Just Beyond the Light for me as compared to writing Dark Days was the fact that for much of the time I wrote it, I didn’t have a clear road map of where I was heading. With Dark Days, the awful recent events of my life provided the previously mentioned classic three act structure—Setup (arrest), Confrontation (imprisonment), and Resolution (exoneration). It certainly wasn’t pleasant to revisit all that stuff while writing the book, but the story was already there for me, very neatly packaged, tidy and preordained. I viewed my job while writing Dark Days as getting from Point A to Point B as artfully as possible. Much to my dismay, this was definitely not the case with Just Beyond the Light.

I did always know how I wanted to the new book to begin; Chapter One, “The Duke,” is about facing mortality—this theme is conveyed through the tale of a terminal fan of my band I befriended during the final months of his life. I also knew I wanted to work in some stuff about surfing at some point, as it is a very important component of my life (in fact, I’m in Costa Rica right now, answering this question in between surf sessions—yeeeewwwww)! But other than death and surfing (“Death and Surfing”… now that’s a good title for something), I didn’t really have any idea of what the book would be about, so writing it actually was a mental road trip of sorts for me. As an author, it’s really hard to get all clever and manipulative and pedantic when you don’t have a clue as to what conclusion you are trying to herd the reader toward. Plus, much like every single other thing of worth I’ve ever attempted in my life, I was scared shitless when I started writing it, and I didn’t want to hide that fear from the reader. However, I am foolhardy enough and in possession of just enough self-confidence (warranted or not) to say, “Fuck it, dude—let’s give ‘er a whirl and see what happens.” That’s just kind of the way I am in general—I realize that this attitude may eventually get me killed (or at the very least, severely ridiculed and possibly publicly shunned), but so far, it’s served me pretty well.

I think the thing that I’m proudest about JBTL is simply that I stuck with it to the end, and I managed to conclude the book in a manner that makes sense… I think… I hope? (Please, please God, let it make sense!) This was a much harder book for me to write than my first one, so really, I’m just happy I got the damn thing done.

On that note: to anyone out there in the trenches, struggling to get to the end of their book, whether it’s your first book or book number one hundred—stick with it and finish that motherfucker.

When you are done, go ahead and give yourself a pat on the back, then give yourself another one from me. You didn’t break, you didn’t give up, you maintained that intense and sustained creative exertion until the end of the road, and while most people don’t have a freaking clue of how hard it is to write a book… I do. And I’m proud of you, goddammit, because you and I are writers, real writers, and in this world of constant asinine digital distraction, we are an increasingly rare breed. Salute to all my brothers and sisters of the pen!

As far as my hopes for the book, obviously I hope it sells a zillion copies— that would be nice, and it’s every writer’s fantasy. But as A) that is highly unlikely and B) I prefer to dwell in reality not fantasy land, my true hope for JBTL is that it will help someone in some way.

Money and accolades are nice, but after thirty years of hacking away at myself and my life for material as an artist, I have long known that beyond any shadow of a doubt the most rewarding part of this whole being an artist gig is when someone comes up to me and says “Hey dude—your song/book/photo really helped me out during a dark period in my life”—those words are pure magic to my ears, a balm for my troubled soul, and I have been lucky enough to hear them many, many times over the years.

I also hope the book encourages the reader to take a look at their own life, to examine their own situation, and ask themself a question: “What are the most effective tools that I have at my disposal, right here, right now, that I can use to improve my own life and to help others?” My tools are writing, music, and photography. What are yours, and what are you waiting for? Go find them, pick them up, and get to work!

For more from Randy, check out his Instagram and this Daily Stoic podcast interview. Randy also writes an extremely readable Substack, Randonesia. You can preorder his new book here.

As always, thank you for reading, especially this last post of the year. I’m wishing you all good things in 2025.

Cat

In fact, if you’re ever in Richmond, Virginia—where he lived for a long time—you might break the ice with natives by asking: “What’s your ‘wow, Randy Blythe is a really nice man’ story?’” I witnessed one myself a couple years ago, at a protest after Uvalde, when this mother came up to thank him for taking a really great picture of her son. Then I snapped this picture of them.

Thanks for the interview, Cat!

Catherine, I have not yet read your post which I shall because your work always proves rich and rewarding. I want you to know that I have been thinking a great deal about you and especially your little one. I hope he was able to enjoy a happy Christmas and that you and your family have a very healthy and joyful 2025. He and you will remain in my thoughts and meditations.